When Porsche’s chief designer Michael Mauer considers the style language of tomorrow, he first has to look much further ahead. Here, he explains how focusing on the future opens up possibilities for the here and now.

Today

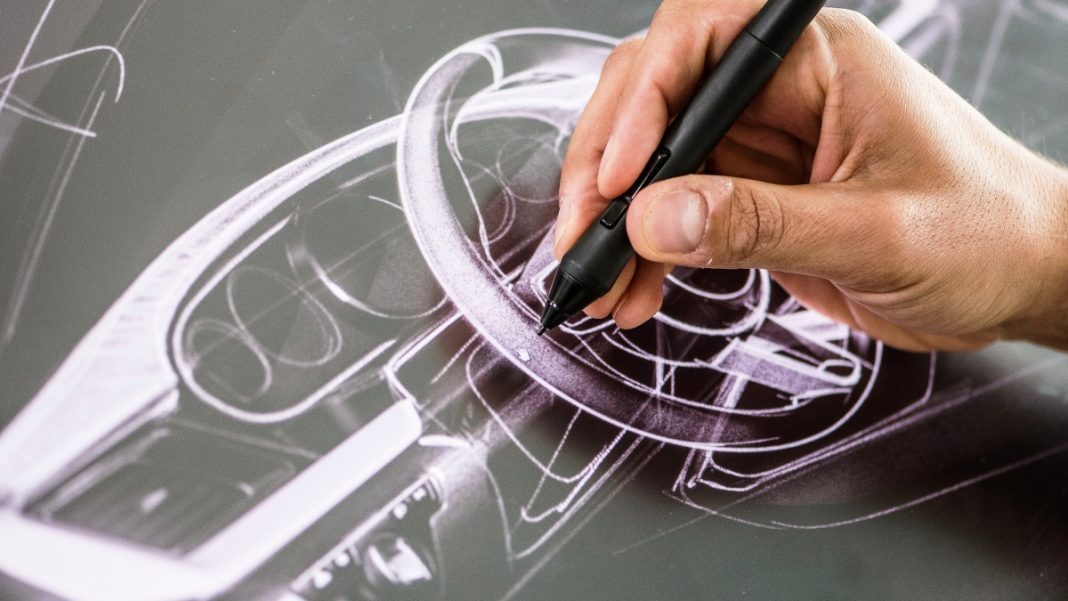

What will a designer come up with tomorrow? Well, first he’ll think about tomorrow. It’s a designer’s job to look beyond the here and now towards the future – more or less constantly. Study how designers think, and you will find that they are not really living in the present, but are already a step ahead. It is comparable to what lawyers call the “fictitious second” – let’s call it the “aesthetic second” of the designer. It is still worth their while to know the shapes of the past and to have analysed their effects, but his or her orientation is forward-looking. It’s true in general, and particularly for designers in the automobile industry.

This special aesthetic second, as a pacesetter of the present, is of course not enough to draw a future Porsche 911 that will hit the road four or five years later. So how do designers recognise what will constitute the contemporary lines of tomorrow?

It’s less myth than mechanics – it’s not the kiss of the muse that creates a formal fascination with the future, but a leap in time. As the American psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz so aptly put it, “The future is not some place we’re going to, but an idea in our mind now. It is something we’re creating, that in turn creates us.” In order to be able to show tomorrow, a designer needs to travel to the day after tomorrow.

The day after tomorrow

The day after tomorrow, an era that lies at least 30 years in the future, is attained in a designer’s mind by looking at developments and considering how these – when taken to an extreme conclusion – could shape the day after tomorrow. Perfect 3D holograms, for example, that could make it possible to travel any distance in the blink of an eye. Or tiny megamotors with infinite free energy at their disposal and an efficiency of over 99 per cent.

To span this enormous leap in time, a technique known as “radicalisation of the imagination” is used. It’s not a question of being just a bit of a visionary; you have to be unrestrained, absolutist, a radical. Doug Chiang, head designer of Star Wars, has perfected this mechanism. It’s how he’s able to think his way into the galactic world of Luke Skywalker.

Once we reach the day after tomorrow, it becomes a versatile space full of possibilities: a space that can show designers radical visions of a future present. Images are created, changed priorities become visible, and ideals can be re-evaluated. What we think of today as having no alternative may be gone by the day after tomorrow. And, what’s more, these visits to the day after tomorrow also change those who undertake the journey. As Grosz points out, traveling through time changes the traveller, too. And it’s this change that is the goal. It gives us new perspectives on how we use things such as cars, cell phones, or money. Enriched with this knowledge, the designer can travel further and back at the same time: into tomorrow.

Tomorrow

By now, designers ought to be very familiar with tomorrow. Tomorrow should now feel like home compared to the faraway scenery of the day after.

In order to do their job and move from the visionary to the concrete – in other words, to define the very concrete shape that will fit perfectly into the brand image and the evolutionary spirit of the times in four to six years’ time – Porsche designers need to become lateral and longitudinal thinkers. This means first ensuring the logical continuation of what already exists and shaping what is beautiful into what is perfect. But just when they have created the highest degree of visual perfection from today’s point of view, designers break this by adding a precisely composed dissonance. I call it the “Claudia Schiffer paradox”.

Near-perfect beauty was embodied for many years by the Chanel model Claudia Schiffer. Indeed she was almost tiringly beautiful. That’s why we designers also add a contradiction to our perfect ideal. In Schiffer’s case, maybe it would have been a little gap between the teeth. It’s contrast that makes charisma: perfection plus contradiction.

A good designer can do this quite intuitively – because designers often think far in advance, but never in a straight line. Their thinking has to be turbulent.